This is not another story about how the shrinking job market for attorneys makes enrolling in law school a bad idea.

The market for lawyers is growing, and the federal government predicts it will continue to do so – at about the same speed as the overall labor market.

The problem isn’t demand, but an oversupply. In the past 10 years, growth in attorney positions has been far outstripped by the number of graduates earning law degrees. A significant portion of those gains is outside large law firms, which means they don’t come with the high salaries some graduates count on to pay for their educations.

All of this makes going to law school a high-risk idea. Whether it turns out to be a bad one depends heavily on individual choice, not just on 18th-century economist Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” steering the labor markets.

To curb the chances of winding up unemployed, or underemployed, with well over $100,000 in non-dischargeable debt, prospective students must be flexible about where they’re willing to work and weigh the quality of their school’s education; how much they need to borrow to pay for it; the odds of getting the job they want afterward, and the salary they’re likely to draw, according to the dozen or more deans and recent graduates interviewed nationwide.

“If you’re someone who really wants to go to law school, you have to go in with your eyes wide open,” said Chris Fletcher, who graduated in 2011 from Northeastern University School of Law in Massachusetts and now works as a law firm associate. “You have to do your due diligence more than you would have at any other time to understand for each prospective law school what is the average debt that students are incurring, what are the average salaries, what types of jobs are they getting and how long is it taking them to find jobs.”

People considering law school need to be brutally honest with themselves about whether they can afford it, just as they should be when buying a home, a point illustrated in the wave of foreclosures nationwide after the collapse of the mortgage market, said Chris Fedorchak, who earned a juris doctorate in 2009 from Villanova University School of Law in Pennsylvania and works in regulatory affairs. Those who decided to stick to houses priced within their budgets fared much better afterward than those who didn’t.

“There needs to be students who are willing to do that with a juris doctorate and say, ‘Wow, this school is great. It’s up against the beach, it’s got a state-of-the-art library and there’s a retired Supreme Court justice who’s an adjunct professor, but it’s $45,000 to $50,000 a year to go here and I can’t afford that, even though I got in, so I’m going to go someplace cheaper,’” Fedorchak said.

There is an alternative, he said: “Decide that ‘I can’t afford law school, period, right now. Maybe I should put it off for a few years until I’m in a better position financially, more mature, whatever, and then I can look at taking the loans out. Maybe I’ll work for a few years, try to save up $20,000 to help pay for a year so I don’t have to take so many loans out.”

STEADY DEMAND GROWTH

Assessing the job market for lawyers and typical pay is a crucial component in making that decision, recent graduates and deans said. It determines not only whether and how quickly the money can be repaid, but also whether law graduates can afford to take a vacation, for example, or buy a house.

“You’re graduating with $180,000 worth of debt, and the opportunities are $50,000- or $60,000-a-year law jobs – that ratio doesn’t work,” said Mitchel L. Winick, dean of Monterey Law, a California-accredited school that’s seen many of its graduates occupy Superior Court judgeships. The average student debt for Monterey’s graduates is about $35,000, which is workable on a starting salary of $50,000, Winick said.

“My rough estimate is that if a student can graduate law school with no more law school debt than approximately their first year’s salary, then the likelihood is they’ll be able to get a job, service their debt, raise a family and build a very rewarding career,” he said.

Consider that calculus along with the growth gap between the attorney job market and the pool of available lawyers, then add the $171,000 average total cost of three years in law school, and you can see the level of hazard involved.

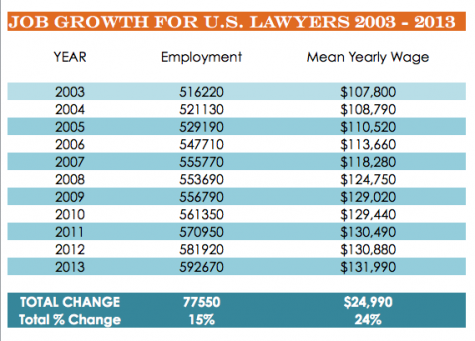

Some 420,000 J.D.s were awarded in U.S. schools in the 10 years through 2012, according to data collected by the American Bar Association. That’s roughly five times the increase in filled lawyer positions during the same period, which the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics pegs at 77,550, excluding self-employed attorneys.

Including them, demand for lawyers will probably grow at about 10 percent a year through 2022, the bureau projected. That’s about 7,480 jobs a year.

Comparing the number of graduates with the number of projected lawyer job openings – which includes positions created through retirement and resignations rather than new jobs alone – narrows the gap. The agency predicts 199,000 job openings through 2022, or about 19,900 a year, still less than half the number of new law degrees awarded.

“For the vast majority of people, it simply doesn’t make sense right now, unless things change,” to go to law school, Fletcher said. “The debts are too high, the salaries are too low and the jobs are too few.”

Fletcher, who began law school in 2008, said he researched employment data as best he could beforehand, though at that time law schools weren’t required to differentiate between full-time and part-time jobs in hiring statistics for their graduates, or show which jobs required passing a bar exam or were temporary. Now they are, which gives prospective students more effective tools.

WAITING ON A MAI TAI

The growth disparity between the job market and the lawyer labor pool has been enabled in part by easy access to federally backed student loans, even in periods when demand for attorneys has stagnated.

“The market forces affect the job market, but not the education market, which is never a good thing,” Winick, Monterey’s dean, said. “An economist would tell you that with a rising cost, but a shrinking market or a changing market price, you’re going to have a problem, and that’s what I think we have.”

Many students borrowing education money assume they wouldn’t be given a loan if the lender considered them unlikely to pay it back, said Mariah Richards, a legal advocate for a battered women’s shelter who graduated in 2012 from Thomas M. Cooley Law School in Michigan. History shows that’s not the case.

“Look at the mortgages,” she said, referring to the collapse of the sub-prime lending market that precipitated a global financial crisis in 2008. “The student loan thing is going to go badly; it’s already going badly. Nobody can pay these.”

Richards, who worked her way through college with $5,500 in loans, was offered a 60 percent scholarship at Cooley. Including living expenses, her law school debt still totaled about $30,000 more than she anticipated.

“I thought that there were jobs out there,” she said. “I thought that I’d be making enough money to make the loan payments. I also did not have a good idea of really what I was doing with the money; I’d be the first to admit that.”

Unable to obtain public-interest work in the post-financial crisis economy in which she graduated, Richards took a job as a bankruptcy attorney earning $500 a week before obtaining her current position, which pays $20 a week less but offers far more satisfying work. She assists domestic-violence victims unfamiliar with the criminal justice system, helping them obtain court protection orders and accompanying them to hearings, though she doesn’t serve as their attorney.

“I couldn’t ask for a better job,” Richards said. “I feel better about this than the stuff that I did when I was on the public defender internship. I feel like I’ve helped more people.”

The law degree, for which Richards still owes about $117,000, wasn’t a requirement for the job. It has been an asset, she says, but a bachelor’s degree would have sufficed.

Many of her classmates also struggled after law school, Richards said. Those who had dreams of high-salaried jobs at large law firms found them quickly dashed. A few students, she recalled, would “say things like, ‘We’re just going to have to get a big corporate job for five years and work really hard and then we’ll be on the beach sipping a Mai Tai out in Bermuda and it’s going to be so much fun.” It never happened, she said, adding: “They’re still waiting for their Mai Tai.”

Richards keeps her own diploma from Cooley wrapped in the frame her mother bought after her graduation. She keeps a reply ready when students considering law school seek her advice: Don’t do it. “I show them my pay stub and my bar card, and then I tell them about the debt and about the job market,” she said.

WHERE THE JOBS ARE

That kind of frustration looms large in a Lawdragon national survey of more than 2,200 law students and graduates. About 28 percent said it wasn’t worth the cost.

“All of legal education has to be ready to respond to the value of a legal education in a very challenging employment market,” said Deanell Reece Tacha, dean of Pepperdine University School of Law in California.

“It is absolutely true that traditional law-firm jobs have dwindled,” she said. “The law firms tell you that. The statistics speak, but that is just a sliver of where lawyers are working.”

Indeed, the decline in hiring at law firms, especially the largest ones comprising 500-plus lawyers, has made the overall market appear bleaker than it is. The percentage of all employed law school graduates in the U.S. who landed jobs at law firms dropped from almost 61 percent in 1985 to about 51 percent in 2012, according to the National Association of Law Placement (NALP), a Washington-based group of legal employers and educators that has been measuring employment of law students nine months after graduation.

The portion of those hired by firms of 101 lawyers or more dropped to 30.5 percent from a 2008 high of 43.2 percent, association data show.

The effects of the drop have been eased by employment in business and industry, which mushroomed to about 18 percent of 2012 graduates hired nine months out from about 11 percent of 1993 graduates. NALP data show that banks and finance companies accounted for the largest number of hires, followed by technology firms and agencies specializing in temporary legal employment.

Taking advantage of the new reality requires graduates to be more flexible about where and for whom they work, deans said. Some law graduates, particularly those at prestigious or urban institutions, have shunned offers they deemed less desirable – from smaller firms, for example, or businesses in less populous states – holding out for what they hoped would be a more lucrative offer from a large law firm in Los Angeles, New York or Miami, school officials and recruiters said.

“I can’t tell you how many would say initially to me, ‘Well, that’s a very interesting job, but I came to law school to work in a law firm so I’m going to wait for that,’” said Brooklyn Law School Dean Nick Allard. “They’re not going to find those jobs.”

Some rule out a temporary, part-time position after graduation, even though temporary-to-permanent employment accounts for a growing portion of hiring, Allard said. The key is thinking differently: Juris doctorate-holders seeking employment will have to be open to going where the jobs are rather than where the jobs used to be, he said.

Graduates refusing potentially good offers has posed challenges nationwide, said Jim Leipold, executive director of NALP, the law placement group. “We see that all the time,” he said. “It’s a difficult economy. Students come in with one set of expectations” and have varying degrees of success in adjusting to an alternate reality.

Law schools also must become more flexible. Placing students with non-law firm employers, who don’t need to replenish a base of junior attorneys and haven’t synchronized their hiring with the academic year, is forcing job-placement offices to develop new operating methods.

“Many law schools have built their placement model around the largest firms, which have this hiring season,” said Maureen O’Rourke, dean of the Boston University School of Law. By contrast, jobs that are expanding, “if those opportunities are open to you, don’t come up in bunches,” she said. “They don’t come up on a regular calendar schedule. Figuring out how to match your people up with them is a real challenge.”

RAISING REVENUE, CUTTING COSTS

That hiring environment has affected salary gains. While growth in the median yearly wage for lawyers hovered around 4 percent in the years leading up to the financial crisis, it’s remained below 1 percent since 2010.

O’Rourke and other law school deans acknowledge the pincer effect created as salary growth dwindled while law school tuition continued to rise. That imbalance can be addressed both by better informing students on how to balance the cost of their degree with their prospective salaries and reducing their expenses.

“You decrease the cost in one of two ways,” O’Rourke said. “On the revenue side, what you would hope to do is provide more financial aid, through either increased philanthropy or increased revenue from other sources. On the cost side, you have to take a really hard look at your structure. For most schools, it’s fair to say that the largest portion of the budget goes to human capital in the form of both faculty and staff.”

Among the factors pushing up staffing costs – and, thus, tuition – is a requirement that nationally accredited law schools offer their faculties tenure to ensure academic freedom. The American Bar Association’s Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar, the government-designated accrediting agency for U.S. law schools, rejected a proposal to eliminate that earlier this year.

In the meantime, some institutions, such as the University of the Pacific McGeorge School of Law and Thomas Jefferson School of Law, both in California, and Vermont Law School have already instituted layoffs. Other law schools have reduced tuition. The University of Iowa is cutting tuition 16 percent in the fall; Ohio Northern University is lowering it 25 percent. Other schools including Penn State and Seton Hall in New Jersey are offering scholarships that effectively accomplish the same thing without making the change universal or permanent. Brooklyn Law froze tuition in the 2014-15 academic year at the same level as this year and will cut it 15 percent in 2015-16.

Another tactic in reducing costs is trimming the time required to earn a degree. At Pepperdine, Tacha set up a two-year program in which students attend classes year-round. While that doesn’t lower tuition, it reduces total living expenses and curbs lost income.

“We have built into it plenty of externship and internship opportunities, so they get that experiential component the same as all our students, and we have built into it as well some additional student services to try to alleviate the strain of going to law school year-round,” she said. “Plus, they get to the bar one year sooner.”

President Obama, who earned his law degree from Harvard University and taught at the University of Chicago Law School for 12 years, also advocates trimming to two years the length of time required for a law degree. “In the first two years, young people are learning in the classroom,” he told Binghamton University students in New York last August. “The third year, they’d be better off clerking or practicing in a firm, even if they weren’t getting paid that much. But that step alone would reduce the cost for the students.”

The total cost for a legal education, based on sticker-price 2013-14 tuition and fees plus living expenses for three years, varies widely in the U.S., from a low of about $76,000 at North Carolina Central University to about $257,000 at Brooklyn Law School, according to a Lawdragon analysis that showed the average is $171,000.

Comparing school costs as well as the availability of scholarships, a form of financial aid that doesn’t require repayment, and the possibilities for part-time work, can help students reduce expenses on the front end. Weighing likely debt against likely salary prospects after graduation is a pivotal indicator of return on investment.

To help navigate the uncertain terrain, law schools including those at Georgetown University, the University of Michigan and Boston University offer financial aid calculators that show students how much they’ll need to earn to repay their debt.

“If you understand what you’re going to be looking at once you get out, and then you factor that into your decision to go, it’s probably not as bad,” said Adam Sticht, who began law school at Michigan-based Thomas M. Cooley, then transferred to Hamline University in Minnesota.

Sticht, who now handles estates and trusts at a small firm in Wisconsin and works part time as an assistant district attorney, paid off his undergraduate loans before starting law school.

He knew that he wanted to stay in the Wisconsin-Minnesota area and switched to Hamline because it was better known in that area than Cooley. Indeed, both Minnesota and Wisconsin are among the top three employer states for Hamline Law graduates, and neither places in the top three for Cooley.

The investment yielded the return he wanted: employment as a lawyer in the area where he grew up. And he loves his work. Still, the cost of a legal education is unrealistic compared with the salaries most new attorneys earn, he said.

“When I got done, I had a little under $190,000 debt for seven semesters in law school,” he said. “The interest accumulating on that is terrifying.”

If not for an income-based repayment plan, Sticht’s monthly payments on law school debt would have totaled $2,100 a month. “When I actually saw the figure that I had to pay back on my exit counseling, I got a knot in my stomach,” he said. “I was a little freaked out. You know it’s going to be bad, but when you actually see the numbers, it’s like, ‘Holy crap.’”

SURVIVING STICKER SHOCK

That kind of sticker shock was a common thread in the experiences of several recent law school graduates. Reducing expenses, whether through careful planning by prospective students or tuition decreases at law schools, is important because it gives graduates more maneuverability in the shifting job market.

If you’re not paying off large loans, “you have more flexibility to decide to pursue a career that doesn’t quite generate as much high compensation,” said Michael Schwartz, dean of the William H. Bowen School of Law at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock. “Hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt is a lot to drag along behind you while you go out into your first real career, as many of the law school graduates are.”

Such debt combined with a legal education system that has long emphasized theory and “learning to think like a lawyer” has proved a daunting challenge for many graduates when they begin looking for work. Some 36 percent of participants in the Lawdragon survey said U.S. law schools aren’t doing a good job preparing graduates to succeed professionally, compared with 32 percent who said they are.

Fedorchak, the Villanova student who graduated in 2009, recalls his dismay when, after failing to find employment, he consulted a school administrator about starting his own firm and was warned against it.

After graduating in May and passing the Pennsylvania bar exam, he had begun pro bono work with clients in mortgage-foreclosure cases. The administrator advised him to keep doing that, build experience and continue looking for employment.

“Looking back, it was the right advice, and it was good advice,” he said. “The problem was that I wasn’t getting paid and I had six figures of student-loan debt. There’s a level of impracticality in dealing with that situation that was economically horrible.”

After the six-month grace period on student-loan repayments expired, Fedorchak shifted his focus from finding work as an attorney to simply finding work and began exploring jobs in regulatory affairs, a field in which he had worked after completing his bachelor’s degree at The College of William & Mary in Virginia.

That experience helped him land a regulatory affairs job in Washington, D.C, and while his law degree may help as Fedorchak advances in his career, it’s of little immediate practical benefit.

“If I were to go to Villanova now, the only way the value makes sense, paying sticker price, is if I was going to have a $150,000-a-year Big Law job out the door,” he said. “To get it to do what I’m doing now, that doesn’t make any sense at all, because I don’t need it. A lot of people in this situation, they don’t really need it.”

Others are starting to reach the same conclusion. Enrollment of first-year law students dropped for the third straight year in the fall of 2013, sliding 11 percent to 39,675, the lowest since 1975, according to data collected by the ABA. That’s a 24 percent decline from the peak of 52,488 in the fall of 2010.

John Denney was well aware of the challenging employment landscape when he began working toward a juris doctorate last fall at the William Mitchell College of Law in St. Paul. He took the Law School Admission Test, or LSAT, after earning a bachelor’s degree in philosophy and political science from St. Cloud State University, and scored high enough to be accepted at several schools.

Denney picked William Mitchell because it was close to home and proffered a 75 percent scholarship, turning down offers from more prestigious institutions that provided less assistance.

“I very much viewed it as, ‘If you’re coming out as your average law student with your average amount of debt, you’re not in a good place,’” said Denney, who plans to focus on transactional and contract law, then use his degree to start his own business, possibly in utility maintenance. In the meantime, he’s been endorsed as the Independence Party candidate for Minnesota’s 6th Congressional District seat, currently held by U.S. Rep. Michele Bachmann.

“You’d better go with an open mind if you’re going to law school – you’d better keep your eyes wide open,” he said. “If you don’t start putting a plan together, you’re going to end up on the other end of this thing with a lot in debt, with not a lot to say. It’s a very high-risk thing, if you ask me, but it can also be high reward, and I’ve always been a risky soul.”

Contact James Langford at (646) 722-2624 or james@lawdragon.com