The Murphy family didn’t make a habit of traveling to the same place twice. So when Gonzaga Law Professor Ann Murphy applied for a second Fulbright teaching scholarship in China, she knew it would be a break with tradition.

Her logic was that China’s rank as the world’s fourth-largest country by area and its diverse population of 1.4 billion make each visit unique.

“I told my brothers and sisters I can’t believe I’m applying for China again because that’s not the Murphy way,” she said in a telephone interview about the most recent grant, which will take her to Shanghai for a year. “But it’s such a huge country, it counts as something different.”

With her first Fulbright scholarship, in 2007-08, Murphy, her husband and two children traveled to Beijing, where she taught English-language law classes at the Central University of Finance and Economics and at the China University of Political Science and Law.

This time, she will teach English-language law classes at the Shanghai University of Finance and Economics. Her husband will accompany her again, but her children – who enrolled at Beijing 55 middle school during the last visit – will both be in college in the U.S. They’ll visit and keep in touch by videophone.

This time, she will teach English-language law classes at the Shanghai University of Finance and Economics. Her husband will accompany her again, but her children – who enrolled at Beijing 55 middle school during the last visit – will both be in college in the U.S. They’ll visit and keep in touch by videophone.

“That’s going to be the hardest part for me; my husband and I are really close to our kids,” Murphy said. “We tried to convince both of them to come on over.”

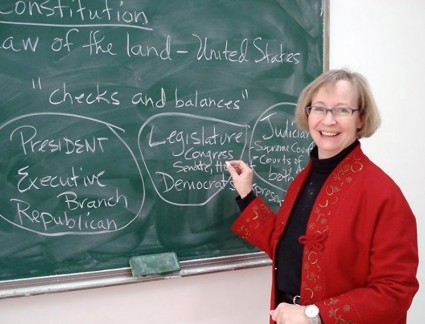

Murphy joined the Gonzaga Law faculty in 2000 after working almost 15 years as an attorney with the Internal Revenue Service. She holds a juris doctorate from DePaul University and bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Western Illinois University.

Her teaching scholarship is one of only seven Fulbright grants for China this year, and she’s the only law professor to receive one. Her stint begins in August, and she’ll return to the U.S. in mid-June.

Winning a second Fulbright was made possible by a change in the program’s rules, which originally allowed applicants to receive only one. Overseen by the State Department, the Fulbright educational exchange initiative was created in 1946 through legislation proposed by the late Sen. J. William Fulbright of Arkansas.

Its core, the Fulbright Scholar Program, sends about 800 American professionals a year to about 130 countries, where they lecture or conduct research, according to the State Department’s website.

To win a second grant under the rule change, recipients must demonstrate compelling circumstances, Murphy said.

RULES OF EVIDENCE

She did so by arguing that her background in teaching evidentiary law would allow her to make a unique contribution as China’s government considers instituting uniform rules of evidence in its courts. Subjects that might be addressed include hearsay rules, the right of suspects to confront their accusers and eyewitness testimony.

“I’m not there to tell you to do it our way, because that’s not appropriate, but I’m there to help in any way I can and indicate why our rules are the way they’re structured and whether that’s working,” she said. “It’s a prime time to be there.”

She doesn’t know yet exactly which subject she’ll teach, since she offered a number of alternatives on the application. At Gonzaga, Murphy teaches in a variety of areas including evidence, individual federal income tax, litigation skills and wills and trusts.

While she says she’s thrilled to be returning to China with her most recent Fulbright, Murphy still remembers how dubious she felt about applying for the first one.

“I said, ‘I’ll never get a Fulbright,’” she recalled. “I mean, I didn’t go to Harvard. I didn’t go to Yale.”

It was a faculty colleague, Mary Pat Treuthart, who convinced her to take the risk. At the time, China was establishing an income tax and Murphy cited her experience at the IRS.

“Lo and behold – I couldn’t believe it – I got it,” she said.

This time, she’ll go with more linguistic skills than she had previously. On the first trip, she relied heavily on those of her husband, an interpreter who speaks Mandarin. She studied the language while in Beijing, and picked up some of the basics.

Reading came more easily than speaking, since differences in meaning are conveyed by tones that Murphy admits she found difficult to distinguish.

“Sometimes, people would just laugh, so I’m sure I was saying just bizarre stuff because I wasn’t using the right tones,” she recalled. “But by the time I finished, I could say ‘fruit,’ I could obviously say ‘hello,’ ‘thank you’ and ‘excuse me,’ and ‘Where’s the bathroom?’

“I could tell a lot of times what people were asking me, but I couldn’t really answer appropriately,” she said. “I’d try and they’d kind of get that look like, ‘What?’”

Contact James Langford at (646) 722-2624 or james@lawdragon.com.