Ronald Weich learned to navigate myriad, and often competing agendas, from two of the art’s best-known practitioners: the late U.S. Sen. Ted Kennedy and current U.S. Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid.

Ronald Weich learned to navigate myriad, and often competing agendas, from two of the art’s best-known practitioners: the late U.S. Sen. Ted Kennedy and current U.S. Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid.

Weich was counsel to Kennedy from 1990 to 1997 and an aide to Reid in the three years through 2009.

Since politics was, and is, an arena where professional success relies on effective negotiation, those pieces of Weich’s resume have served him well in subsequent roles. In 2009, President Obama appointed him assistant attorney general for legislative affairs and three years later, he became dean of the University of Baltimore School of Law.

“I did learn a lot in the Senate that helps me today,” Weich said in an interview last week in the law school’s new Charles Street home, a glass-and-steel high-rise with a profile that conjures both the 1980s-era Rubik’s Cube and the Lego Group’s toy building blocks.

Working for Kennedy, nicknamed the “liberal lion” of the Senate, gave Weich an opportunity to observe the late legislator’s ability to work with people of all political stripes. Indeed, Republican Sen. Orrin Hatch of Utah was among the speakers at Kennedy’s memorial service in 2009.

Kennedy “never backed down from core principles, but he always was willing to take half a loaf to move the ball forward,” Weich said.

While the dean’s work with Kennedy often involved marathon late-night sessions drafting bills and amendments, his work with Reid was more strategic: advising the leader on managing floor debates.

Just as Reid must persuade a caucus of Democratic senators who don’t work for him, and have an independent right to their positions, to follow his leadership, “so it is with a dean and a law faculty,” Weich said. “They don’t formally work for me; I can’t fire them if they’re tenured. But we find a common goal and motivate people to march toward it.”

When Weich joined the law school in 2012, it was 87 years old and preparing to move from the building that had been its home for almost 30 years. The new 12-story site began hosting classes in the summer of 2013, and as of the fall, the school had 976 students

“I’m constantly building coalitions to try and accomplish things, working with different stakeholders, asking myself, ‘Who do I need to bring on board to get to the place where I want to go?’” he said.

Weich, who began his career as a prosecutor in the Manhattan district attorney’s office in 1983 and later worked in the Washington office of Zuckerman Spaeder, moved into academia at a time when law schools are grappling with declining applications amid an oversaturated job market.

Nationwide, first-year enrollment dropped 18 percent in the 10 years through the fall of 2013 at the 200-odd law schools accredited by the American Bar Association, according to a Lawdragon analysis.

“When I was looking at this over two years ago, the depth of the challenge wasn’t clear to people,” Weich said. “The applications were already going down, and the enrollment, but it wasn’t as clear as it is now. So I can’t say that I was rushing in to solve the crisis. But I just had the sense that it was a place where I could do good.”

LAWDRAGON: What drew you into legal academia?

RONALD WEICH: I’ve done lots of other things in the law, and I wanted to make a difference in the next generation of lawyers. This is a way to really influence the legal profession for good, to educate students who are going to be effective and ethical and committed to the public interest.

I was especially attracted here because as one of two law deans in the state (the other institution is the University of Maryland’s Francis King Carey School of Law), I’m automatically involved in all kinds of interesting access-to-justice issues. You know, the two law deans automatically get appointed to all the committees, which is great. You have a voice in those issues.

LD: What did you learn about UB Law after arriving? Is there anything you wish you’d known about the role?

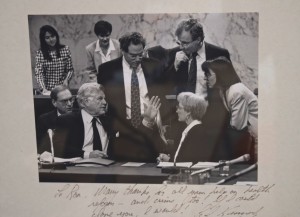

A photo of Ron Weich with Ted Kennedy, hanging in Weich’s office, includes an inscription from the late Massachusetts senator that reads in part: “If I could clone you, I would.”

RW: You never know about any job until you actually inhabit it. This job in particular was new to me in two ways: First of all, I had not been in legal education before; I came from practice. And I did not know University of Baltimore. I’d spent time in Baltimore as a practitioner, but had not obviously worked at the university, so there was a lot to learn.

It’s a fabulous school. It has a very well deserved, powerful reputation for excellent practical learning. Our alumni base is very loyal and because we are one of only two law schools in the state of Maryland, we’re very visible, and UB graduates are throughout the community: successful practitioners, judges, legislators, businesspeople. If you ask even non-UB graduates in the community about UB, they’ll say, “Those lawyers who went to that school know their way around, have good practical judgment and they’re hardworking and tenacious.” That’s a fabulous reputation, and that’s something that I learned really after getting here.

LD: The law school moved into this state-of-the-art structure not long after you came on board, from a building that was about 30 years old. How did that change the educational environment?

RW: I’m so lucky, because it was under construction as I arrived, literally three-quarters of the way done. So we had one year in the old building, and then over here. But the money was already raised for it – it was conceived, designed and basic choices had been made and we just waltzed in. It’s been an interesting and fun challenge thinking about how to leverage the building. It is a wonderful anchor in the neighborhood and in the community, and we want to make sure that people know what’s going on inside this dramatic space.

We want the education to be as contemporary as the architecture. The classroom technology is much more advanced. This past semester, I taught a legislation class, and you really can put on a multi-media show, and it can be very dynamic and interactive. That kind of technology didn’t exist in our old building. There’s also much more common space, places for students to be, to study, to talk with each other and that is very welcome. It’s a glass building, so it’s transparent, and you feel the energy from what everybody is doing. You see all the different activities, and it literally creates its own energy. It’s contagious. I feel that every time I ride up in the glass elevator: I see the classrooms here and the moot court teams practicing, the activity as journals are being edited and the faculty offices. You feel the life of the school on one elevator ride.

LD: UB is not only one of two law schools in the state, it’s one of two law schools in the same city. What distinguishes UB’s law school from the University of Maryland’s?

RW: We are friendly competitors; obviously, there are students who apply to both. Maryland has a different profile – its curriculum has a more national orientation. Here, we proudly have many courses in Maryland civil procedure and Maryland criminal procedure, and naturally, our clinics are working in Maryland state courts.

UB Law was founded in 1925, and the experiential history goes to the beginning. Maryland was always the theoretical, high-minded place, and UB was practical skills. Over the years, long before I got here, UB Law really acquired a reputation for excellence and not just access. Now, it’s both. The night program, which was a very dominant part of the school in its early years, is still important, but it’s about a fourth of the students.

Today, if you know that you want to practice in Maryland or the surrounding region, we have the network that will enable you to succeed. We’re proud of our network of alumni and judges and lawyers in the community who help our students succeed.

But we also collaborate with the University of Maryland on a number of projects. For example, we have a shared summer-abroad program in Scotland that’s ongoing right now, and there is a junior faculty scholarship workshop where our junior faculty and their junior faculty get together to discuss their scholarly projects and present papers.

LD: Law schools nationwide are working to adapt to the tighter job market and ensure that students have the tools they need to compete. What is UB doing, and what do you see as the key to success for recent graduates?

RW: We always recognized that you need to provide practical skills in school, not just send them off to the law firm to get trained, but we’re doing more of it in different ways: expanding the clinics, expanding internships, integrating the Moot Court program – which is very successful here – into the overall curriculum. All of those things are important, but beyond those, students need to hustle more for jobs, let’s be honest. It used to be handed to you on a silver platter, and now they need to be out there doing internships, clerkships, taking pro bono opportunities. Many of our students do pro bono work and it’s a way to get known, to establish relationships, and we help them with that. We focus on professionalism here, so it’s not just your legal ability, it’s how your present yourself. Fundamental skills like public speaking and writing skills are terribly important.

Our legal research and writing is integrated into a doctrinal class. At other schools, it’s a separate legal writing class and students kind of reluctantly go off to learn legal writing. Here they learn it in the context of learning torts, criminal law and civil procedure, so it’s more live, it’s more relevant. We think it’s a very successful model. It also means that they’re learning legal research and writing from the full-time tenure-track faculty.

LD: As applications decline, some law schools are opting to admit fewer students to maintain their academic standards. What is UB’s position on that?

RW: We’re doing the same. I think it’s the only sensible reaction to the situation. Each of the last two years, we were down a little less than 20 percent and this year, applications were down 10 percent. Two years ago, our first-year class was 350 students, last year it was 287 1Ls, and this year we expect to be around 240 or 250. We continue to intentionally right-size the school, because it’s important to make sure that you’re maintaining standards and admitting students who are going to succeed, and you’ve got to take account of the legal marketplace. The jobs are not available for 350 first-year law students. I really think it’s the responsible path to shrink the school in reaction to the market forces.

LD: What does that mean for the school’s finances?

RW: We have good support from our university – it’s much harder for independent schools that don’t have that to rely on – and we have very loyal alumni. I think that there are schools where the finances are more desperate. Here, we’re obviously being prudent about spending, but we’re still able to have hired two new faculty members, a new library director and we’re starting a veterans advocacy clinic. This is still a school that’s forward-leaning. We’re not in a defensive crouch.

LD: Are you seeing any signs of a broader turnaround?

RW: Our applications, as I said, were down less this year, so that suggests a leveling off. In terms of employment, we continue to do pretty well, not as well as, say, 10 years ago, but we’re holding our own.

One thing about the jobs being less plentiful is that the people who are applying to law school really want it. It used to be that you applied to law school if you couldn’t quite figure out what else to do. Many of my classmates were like that. Now, after all the very valid press about the changing profession, the people who apply are committed to being lawyers.

LD: In what new fields do you see demand for lawyers as some traditional jobs, such as document review, dwindle?

RW: The Internet creates new legal challenges, so cyber-law, Internet privacy and intellectual property as it pertains to electronic media. These are all new fields in the law. International law is becoming, I think, more prominent because the economy is more global.

LD: What do you do outside the school when you’re not being dean?

RW: I enjoy running, tennis, theater, rooting for the Orioles and Ravens, and spending as much time as possible with my 11- and 14-year-old daughters.

Contact James Langford at (646) 722-2624 or james@lawdragon.com.