Infilaw, the private equity-controlled firm that agreed to buy the Charleston School of Law, will seek final approval of the deal from South Carolina’s regulators in early June after a rebuff this week.

The purchase, for an undisclosed amount, was announced in August 2013 and is contingent on Infilaw’s obtaining an operating license from the state Commission on Higher Education, which oversees colleges and universities. While commission staff recommended that the commission’s subcommittee, the Committee on Academic Affairs and Licensing, sign off on the transaction, the politically appointed panel voted 3-1 Monday against doing so.

“We are obviously disappointed with the decision,” Kathy Heldman, a spokeswoman for Naples, Fla.-based Infilaw said in an e-mailed statement. “We are confident that we provide the brightest future for continuing the proud traditions and commitment to excellence of the Charleston School of Law. We look forward to demonstrating our commitment to the school to the full commission.”

The committee’s decision followed vocal opposition from alumni, students and faculty of the school, which was founded in 2003 by five Charleston lawyers and judges. Although a for-profit institution from the start, the school was to be community-based and emphasize public service, according to statements at a public hearing on the sale.

In July, two of the founders decided to retire, and the remaining three bought them out. Afterward, Robert S. Carr and George C. Kosko, both former U.S. magistrate judges, opted to sell the school to Infilaw, overriding partner Edward Westbrook, a Charleston-area attorney.

Infilaw, which currently operates the Florida Coastal School of Law in Jacksonville, the Charlotte School of Law in North Carolina and the Phoenix-based Arizona Summit Law School, “has the financial wherewithal and managerial skills to take this school to the next level,” Carr said during a public hearing in North Charleston last week.

Charleston Law posted bar-passage rates higher than 70 percent for each of the three years through 2012, falling short of the average state bar-passage rate, though it lagged behind the University of South Carolina School of Law, which costs about $50,000 less over the typical three-year law school term.

“The legal landscape looking out at the future is daunting,” said Kosko, who urged regulators to approve the sale to Infilaw, which is owned by Chicago-based private-equity firm Sterling Partners. “The technologies that are going to be required in the future are far different than those that we grew up with. This is going to the require the investment of capital, significant capital.”

Charleston Law can meet such financial and academic challenges without Infilaw, even though it offers the most lucrative option for the founders, Westbrook, the third partner, argued at the hearing.

“I am willing to continue financially to back the school,” if Infilaw doesn’t win the license or backs out of the deal, he said. “We’ll carry on in the way we started, as a community-based law school for the students and not for the founders.”

The 11-member commission is scheduled to consider issuing a license to Infilaw at its meeting June 5, said Deputy Director Julie Carullo.

Faculty, alumni and current students have all expressed concern that the school’s reputation, and the value of its degrees, would dwindle under Infilaw.

In the fall of 2013, the school had a far lower admissions rate than the Infilaw schools and a first-year class that was about half the size of the smallest of the acquirer’s schools.

“For us to remain what we are, we have to stay on our own,” Julian Ferguson, a Charleston student, said at the hearing. “We don’t need to be infused with some new technology, and we don’t need 1,000 students to be relevant. What makes us relevant is that good old Southern hospitality, the work ethic that each student puts in there and the family environment that you will not find at any other law school in the nation.”

A HIGH COURT RULING

Work, and the amount of it required for a law degree, was also on the minds of some Virginia law students.

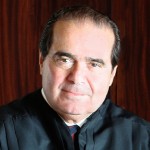

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia used his commencement address at William & Mary Law School to talk about whether his audience had wasted one of the three years they spent there.

His conclusion: They had not. A proposal by the American Bar Association’s Task Force on the Future of Legal Education that law students be allowed to take bar exams after two years of study, rather than three, is misguided, he said.

“It seems to me that the law-school-in-two-years proposal rests on the premise that law school is – or ought to be – a trade school,” Scalia told the graduating class of about 270 on May 11. “It is not that. It is a school preparing men and women not for a trade but for a profession – the profession of law.”

Being “learned in the law” as a whole rather than an expert in just one area is good because “that is what makes you members of a profession rather than a trade,” said Scalia, 78. It also has practical value: “the lawyer who is familiar with many fields can apply the ancient learning or the new developments in one field to another,” he said.

The three-year term appears to be working for William & Mary students: Its graduates have topped state averages on Virginia and New York bar exams for the two most recent years for which data were available. More than 70 percent of them landed jobs as full-time lawyers in 2012 and 2013, according to Lawdragon data.

Unsurprisingly, Scalia’s opinion on shortening the length of law school is directly at odds with President Obama’s, a fact that the justice pointed out himself. He conceded that the debate about shortening law school was prompted by massive increases in cost that have priced many would-be students out of the market.

His own alma mater, Harvard, charges annual tuition of $53,000 now compared with $1,000 a year when Scalia, who earned his degree in 1960, was a student.

For law school to remain three years, costs will have to be cut, he said. Tuition at many schools must be lowered, which may entail shrinking faculty sizes, increasing teaching loads and cutting salaries.

“The graduation into a shrunken legal sector of students with hundreds of thousands of dollars of student debt, nondischargeable in bankruptcy, cannot continue,” he said. “But for the moment, for you graduating students who have had what I consider not the luxury but the necessity of soaking in the law for three full years, and for the parents who have paid for that experience, welcome to the ranks of – not tradesmen, but men and women learned in the law. Congratulations.”

TOO MANY LAWYERS?

A broader swath of the public isn’t so eager to offer congratulations: It’s the opinion of many in the U.S. — including a large segment of participants in a Lawdragon survey — that the country already has too many people who are learned in the law.

About 43 percent of survey respondents said the U.S. has an overabundance of lawyers when asked about the state of the U.S. legal profession.

While that assessment didn’t win a majority vote, it did garner the largest bloc: 996 votes out of 2,329. The next biggest group, 591 voters or 25 percent, said the total number of lawyers isn’t a problem but the need to make a lot of money is.

“There need to be more attorneys serving the public good and less who desire only to practice non-public interest law,” wrote one of the survey-takers. “The problem is that law school is so expensive, schools are not reducing tuition to make it affordable, and thus the problem will not get better until the price of law school comes down.”

Want to share your opinion? You can take the survey here.