A record drop in scores on the standardized bar exam used in almost every state — forcing thousands of prospective lawyers to retake the test — is drawing scrutiny from law school deans nationwide.

A record drop in scores on the standardized bar exam used in almost every state — forcing thousands of prospective lawyers to retake the test — is drawing scrutiny from law school deans nationwide.

Among their questions are whether the biggest slide in almost 40 years indicates technical flaws in the test or the scoring as well as whether the exam is keeping pace with a rapidly changing curriculum.

It’s a crucial question for the legal education industry, as enrollment at the nation’s 200-plus law schools slides amid steadily increasing tuition and a lackluster job market. Law schools that have worked to better position their students to find employment as attorneys now find graduates facing a higher hurdle just to get licensed.

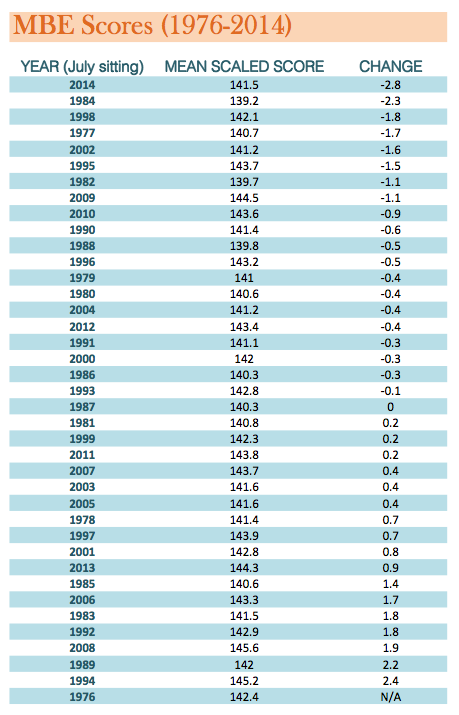

The mean scaled score on the July 2014 Multistate Bar Exam, adjusted to account for differences in difficulty from one year’s test to the next, dropped 2.8 points to 141.5, according to a Lawdragon analysis. That’s not only the biggest drop in July exams from 1976 to 2014, it’s more than double the average year-to-year change.

“We saw how big the fluctuations were, and I thought that there was something very suspicious that I wanted to get to the bottom of,” said Brooklyn Law School Dean Nick Allard, who wrote a letter to the test’s administrator questioning the results and joined 78 of his peers in a request for a thorough review.

“I wanted an explanation for what happened this year so that we know what to do, if it’s something that we should be doing or the students should be doing,” he said. “I want to find that out and so does every other dean.”

‘WE NEED LAWYERS’

The National Conference of Bar Examiners, the 83-year-old not-for-profit that creates the twice-yearly exam, is continuing to study both the test and how it was administered but so far has found no anomaly that would explain the drop, President Erica Moeser said in a telephone interview.

“The reason this matters is because we need lawyers,” Allard said in an interview. “We need more new, energetic, motivated lawyers and here’s why: Look at the mess we’re in, from Ferguson to immigration issues that rip us asunder to gun issues to Ebola.”

Throughout U.S. history, he said, lawyers have helped provide solutions to problems such as the shooting of an unarmed black teen by a white Ferguson, Mo., police officer after a confrontation. The case sparked waves of protests, sometimes violent, that spread around the country.

“Lawyers have always been interwoven into the fabric of our complex country, and they have provided the flexibility for us to stretch and grow and survive,” Allard said. “So if we are somehow constraining and choking off the supply of new lawyers, we are shortchanging ourselves, and that’s where it matters.”

Indeed, fewer lawyers passing the bar would exacerbate a slide in law school admissions. Enrollment of first-year law students dropped to 39,675 in the fall of 2013, down 24 percent from its peak in the fall of 2010. It was the third straight decline. Final figures for this year aren’t yet available, although decreases in the number of people taking the Law School Admissions Test point to another drop.

The shift reflects both high tuition, which at full price averages $171,000 for three years at the nation’s 203 American Bar Association-accredited law schools, and cuts at large law firms, which typically pay the highest salaries to entry-level lawyers.

LEGAL EDUCATION CHANGES

While law schools and other market observers have pointed to increasing demand for attorneys willing to work in rural communities and with indigent clients, such jobs don’t provide the income necessary to repay student loans that often total more than $100,000.

That context heightens the importance of the drop in bar-exam scores.

“The most interesting thing is that this change is taking place while many law schools are adding more interdisciplinary courses and more skill-based experiential learning offerings,” said Jocelyn Benson, dean of Wayne State Law in Michigan and one of the group letter’s signers.

“With that, it raises the question of whether or not, given the changes in legal education for the past few years, the National Conference of Bar Examiners should also reevaluate what it’s testing to see if it is best tied to what we need to evaluate to license the next generation of attorneys,” Benson said.

The score fluctuation also highlights a related concern: The challenges in using a national exam as a skills gauge in jurisdictions with significantly different legal codes.

“There’s certainly room for conversation as to whether the national exam and what it tests is the best method nationally for evaluating lawyers,” Benson said. “Especially when the law can be very different from state to state and you have one national exam that everyone takes and various different schools and educational environments that, perhaps, don’t emphasize what’s tested on the national bar exam as much as they emphasize what is needed in their particular state.”

While Benson still believes a national exam is useful, she said there may be better ways to design it to reflect the variations in law and licensing requirements from state to state.

Such differences are among the factors that fueled demand for bar-exam preparation courses that cost thousands of dollars and are frequently necessary to cover gaps between what students learn in law school and the topics covered in licensing exams in the states where they want to practice.

TEST WITHIN A TEST

“That’s a hard reflection of the disconnect between what the test is examining nationally and what the schools have individually or collectively decided they need to give their students to best prepare them to function in the legal market in their state,” Benson said.

It’s important, she said, for law school deans and state bar examiners to have “a collective, ongoing conversation about what we are doing together to adjust to the changing legal market so that we can reexamine all of the things that we’ve done for decades and collectively challenge whether they remain the best method of training, evaluating and licensing attorneys.”

The Multistate Bar Exam, given in both July and February, is typically one component of state bar exams that may last as many as three days and include essays and professional responsibility reviews. While the National Conference scores the test, individual states determine what constitutes a passing grade and whom they license.

A new test is given at each sitting. The exams include a set of questions from previous years that don’t affect the scores but enable reviewers to compare candidates from different periods, a gauge Moeser referred to as a “mini-test within a test.”

If students this year performed similarly to their peers last year on the mini-test, for example, but fared worse on the brand new material, that might indicate a difference in difficulty that would prompt administrators to adjust scores upward in order to equate the test over time.

“It’s like building a structure, where you put the top block on and if you move one block, everything collapses,” Moeser said. “The assembly of this equating set is a very demanding exercise and one of my questions to the people who work here was, ‘Is there absolutely anything you did, even something minor, that might have, downstream, altered the outcome?’ and the answer was, ‘No.’ But the question had to be asked.”

The more than six-dozen deans who joined the group letter authored by Kathryn Rand of the University of North Dakota School of Law want to see for themselves how the review of the test is conducted as well as what it finds.

“The methodology and results of the investigation should be made fully transparent to all law school deans and state bar examiners,” they wrote in the Nov. 25 letter. “In particular, the investigation should examine the integrity and fairness of the July 2014 exam as well as the overall reliability of the multistate components of the exam.”

The deans also want an independent review of the test and are asking the National Conference to turn over all data necessary for an expert to conduct one.

GETTING IT RIGHT

The questions posed in the letter are “very valid questions, and questions that should be answered,” said Erwin Chemerinsky, dean of the University of California-Irvine Law, who wasn’t among the signers. “There should be some more transparency, and we should get some explanation for why the decrease, but I think it’s a mistake to say, ‘Well, it’s because legal education has changed,’ or ‘It’s because the bar exam has changed’ without knowing more,” he said.

The debate throws into sharp relief differences in the overlapping missions of law schools and bar examiners, one to train and educate potential lawyers and one to gauge how well those holding a degree meet the standards of states where they’re seeking a license.

The National Conference has undertaken a variety of tasks associated with the latter mission since its formation in the early 1930s, under the auspices of the American Bar Association’s Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar.

With early funding in the form of a $15,000 grant from the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, the group began regular publication of “The Bar Examiner” magazine and later added character and fitness assessments of attorneys for state bars, according to Conference archives.

It introduced the standardized Multistate Bar Exam in 1972, with 200 multiple-choice questions, to aid state bars that lacked the resources to provide timely scoring by hand for a rapidly increasing pool of candidates. Those state bars were already facing significant delays between administering tests and announcing results, according to the archives.

The first exam was used by 19 states including New Jersey, California and Florida, according to the archives. The costs were partly covered by a $125,000 grant from the American Bar Foundation, and organizers proposed charging states a fee based on the number of test-takers to cover the costs of later exams.

“Our job is to create a fair test and to score it correctly,” Moeser said. “Everybody talks about what’s in your wheelhouse – that’s in our wheelhouse.”

Doing the job properly matters to everyone, particularly to the bar applicants taking the test, she said.

“We believe we’ve gotten it right,” Moeser said. “Had we determined that we had not gotten it right, we would have acknowledged it and corrected it. That’s what you do. The institution has integrity, and our best efforts to check and recheck have failed to yield any indication this was done incorrectly.”

Contact James Langford at (212) 742-8726 or james@lawdragon.com.