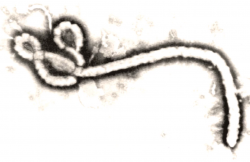

Tradition called for naming the virus that Dr. Peter Piot identified in 1976 after the Zairian village where it first appeared, but the Belgian doctor feared that would stigmatize both the small community and its inhabitants.

Instead, he named the virus – which causes hemorrhaging and fever – after a river: Ebola. His concern proved prescient. Four decades later, the largest outbreak of Ebola to date has stigmatized entire African countries, with some U.S. politicians advocating travel bans and seeking to quarantine American aid workers who have treated the virus’s victims.

UC, Irvine Law Dean Erwin Chemerinsky noted that in the current crisis there is no medical basis for quarantining individuals until they are symptomatic.

The reaction reflects historical social responses to epidemics, from 14th-century Europe’s Black Plague to cholera outbreaks among America’s Irish immigrants and early stages of the AIDS epidemic, according to health and legal scholars in a panel discussion last week at the University of California, Irvine School of Law.

The first event conducted by the school’s new Center for Biotechnology and Global Health policy, the panel focused on the implications of U.S. handling of the outbreak for future health crises.

“The way in which Ebola has been politically approached makes no sense as a medical issue and as a public health issue; it’s really important to separate the politics of all this from the real health concern,” Michele Goodwin, who moderated the panel and will be the center’s director, said in a telephone interview afterward.

“To what extent are Americans willing to trade their privacy for a sense of feeling more secure in their homeland, when Ebola has had a much more profound impact a continent away?” she asked.

‘THE HOT ZONE’

The popular culture’s reaction has been disproportionate to the magnitude of the threat in the U.S., the scholars noted, with many Americans drawing their understanding of the virus from the news media, books such as Richard Preston’s “The Hot Zone: A Terrifying True Story” or epidemic movies such as 1995’s “Outbreak,” about an airborne disease.

What’s missing from the debate is education, said Dr. George Woods Jr., president-elect of the International Academy of Law and Mental Health.

The virus is “actually not highly transmissible, unlike influenza or measles, where I could sneeze if I were infected and infect people,” Andrew Noymer, an associate professor of public health at UC-Irvine, told the panel’s audience.

Ebola is transmitted only when infected blood or body fluids make contact with broken skin, such as a cut, or with mucous membranes, he explained. There’s no evidence that the virus – which originated in the animal kingdom, probably in fruit bats – can be carried through the air, he said.

An infected person isn’t contagious until the onset of symptoms, which can include fever, severe headache, diarrhea, vomiting and unexplained bleeding or bruising and may appear 2 to 21 days after exposure, according to the Atlanta-based federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The people most likely to misunderstand the virus’s potential threat “get all their information from places that don’t discriminate, that don’t allow them to understand the critical thinking component that is required to keep things like Ebola from overcoming us emotionally,” Woods said.

FOUR H’S

“The one thing about delusions is that they always have a kernel of truth,” he said. “It’s not as though they just come out of nowhere. There’s always this nubbin of reality that’s overwhelmed by this ocean of irrationality.”

In the 1980s, for instance, press coverage in the early stages of the AIDS epidemic focused on the so-called Four H’s, groups believed to be carriers: Haitians, homosexual men, heroin users and hemophiliacs, Noymer said.

Three of the four groups lived largely in the margins of U.S. society and were blamed, to a degree, for their own infection.

“I want you to reflect on the status of those groups in 1980s America,” Noymer said, “and consider why we sort of stigmatized these groups among all others.”

It was far from the first time that people in positions of little power had been blamed for an infectious, deadly disease.

A cartoon depicting reaction to the arrival of a ship carrying passengers exposed to cholera, shown at the UC-Irvine conference.

More than a century earlier, Irish immigrants and blacks who lived in the poorer sections of New York City, had proved most susceptible to cholera, and debate arose among social leaders as to whether “the disease was a divine punishment for sin,” according to an online archive produced by the New Media Lab at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York.

Nativists, meanwhile, seized on cholera prevalence among immigrants as a reason to keep them out of the U.S., according to the archive.

During the current Ebola outbreak, Republican U.S. senators, including Chuck Grassley of Iowa, Marco Rubio of Florida and Pat Roberts of Kansas, proposed a temporary ban on new visas and revocation of current ones for residents of Liberia, Guinea and Sierra Leone as well as any other countries designated by the disease control centers as having “widespread transmission” of Ebola.

TRAVEL BANS

That could affect as many as 6,300 residents of Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea who received visas from the State Department from March through September, according to a Nov. 20 statement from Grassley’s office.

“To protect our security, we must stop Ebola at its source,” Grassley said. “The fact of the matter is that these countries simply don’t have the standards in place to properly screen travelers entering the U.S.”

The outbreak, the biggest in history, has infected more than 15,000 people and killed about a third of them, according to the CDC. Four people have been diagnosed in the U.S., including a Liberian man who died.

Aid workers, even when not infected with the virus, have encountered heightened concerns themselves. A Maine nurse, Kaci Hickox, publicly fought efforts by Gov. Chris Christie to quarantine her in New Jersey after a return flight from West Africa and by the Maine governor, Paul LePage, to do the same when she returned home. In that case, a Maine court rejected the state’s efforts to restrict travel by Hickox, who had no symptoms of Ebola.

“It’s so important that decisions to restrict civil liberties be based on scientific and medical evidence,” Erwin Chemerinsky, dean of the UC, Irvine School of Law, said during the panel.

“Thankfully, Ebola can’t be spread through casual transmission, and thankfully, people are not infectious until they become symptomatic,” Chemerinsky said. “This would be a very different conversation, in terms of the law, if those facts weren’t true. But in light of those facts, you can say there is no basis for quarantining of individuals until they are symptomatic, because they can’t spread the disease.”

The typical standard for quarantines, Chemerinsky said, is that the state must show a clear and immediate threat to public health and individually assess people affected by the order to determine that they pose a risk to others.

“It is so important now, when we’re not really facing the spread of a communicable disease in this country, to establish the clear legal principles,” Chemerinsky said.

‘ESSENTIAL’ QUARANTINES

“None of us can deny that there are instances where quarantine has been essential in the past and may necessary in the future,” he said. “But let’s be clear: It’s only appropriate when there’s a clear and immediate threat to public health, there’s no other way to protect public health and we’re only quarantining those where there’s demonstrated scientific and medical evidence that would warrant it.”

Public health concern and political opportunism can be a toxic mix, producing laws and policies that are ineffective at best and counterproductive or even harmful at worst, the scholars said.

“There are certain patterns you can see in regard to law and medicine,” noted Goodwin, the center’s director. “If it happens to be the hysteria of the moment, we will make law that addresses that hysteria. The problem with us making law around one hysteria is that it often is not scientifically based and you find that it’s not very helpful.”

The Rev. Jesse Jackson, a civil rights activist and former U.S. presidential candidate who joined the forum, agreed.

“More people in America die from flue than die from Ebola,” he said. “When politicians take over and run their machinery on science, it’s always a disaster.”

Contact James Langford at (212) 742-8726 or james@lawdragon.com.